Credit: Tim Matheson

At Studio 16 until April 18, 2015

www.universe.com or cash at the door

Posted April 13, 2015

Written by Hiro Kanagawa, Indian Arm is the first script to come out of Rumble Theatre’s new commissioning program. Very loosely basing his play on the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen’s Little Eyolf, Kanagawa retains some of the same names – Alfred (Gerry Mackay), Rita (Jennifer Copping) and Asta (Caitlin McFarlane). But Ibsen’s Rat Wife is a Tsleil-waututh woman called Janice (Gloria May Eshkibok), referred to early in the play as the Mouse Woman, and Eyolf becomes Wolfie (Richard Russ).

Wolfie is appropriate since Eyolf, in Norwegian, means ‘wolf’ and the Tsleil-waututh people are Children of Takaya or ‘wolf’ in Halkomelem, the traditional language.

Credit: Tim Matheson

Beyond the characters’ names, however, there are some essential parallels: the central couple in both plays – Alfred and Rita – is raising a ‘challenged’ child, resented by its mother Rita. The father, Alfred, is a writer who has been until the beginning of the play, emotionally and often physically absent from the family. And there is a tragedy that throws Rita and Alfred into a highly charged confrontation and possible reconciliation.

It is this hugely emotional atmosphere that links Indian Arm most significantly to Little Eyolf. The play begins at a fairly high pitch with Rita bitching to her half-sister Asta about Alfred and it goes up from there. It’s relentless – as is Ibsen’s original.

Drew Facey’s staging is exquisite with a grey and leafless grove of birches stage right and a shabby cottage interior stage left. The overall effect produced by lighting designer Conor Moore is grey and blue and shadowy – very Indian Arm in the rain.

Director Stephen Drover assembles a very strong cast for this world premiere. Gerry Mackay, always a powerhouse on stage, is a forceful but troubled Alfred who, recognizing his limitations as a writer, is now prepared to become a real father to Wolfie. Too little, too late.

Jennifer Copping’s Rita begins as a pissed-off wife, left alone to care for their adopted, First Nations, mentally challenged son. But her frustration leads to an almost psychotic break especially when Alfred turns to her younger sister Asta for solace. Caitlin McFarlane’s Asta is the closest thing to ‘normal’ of this conflicted trio.

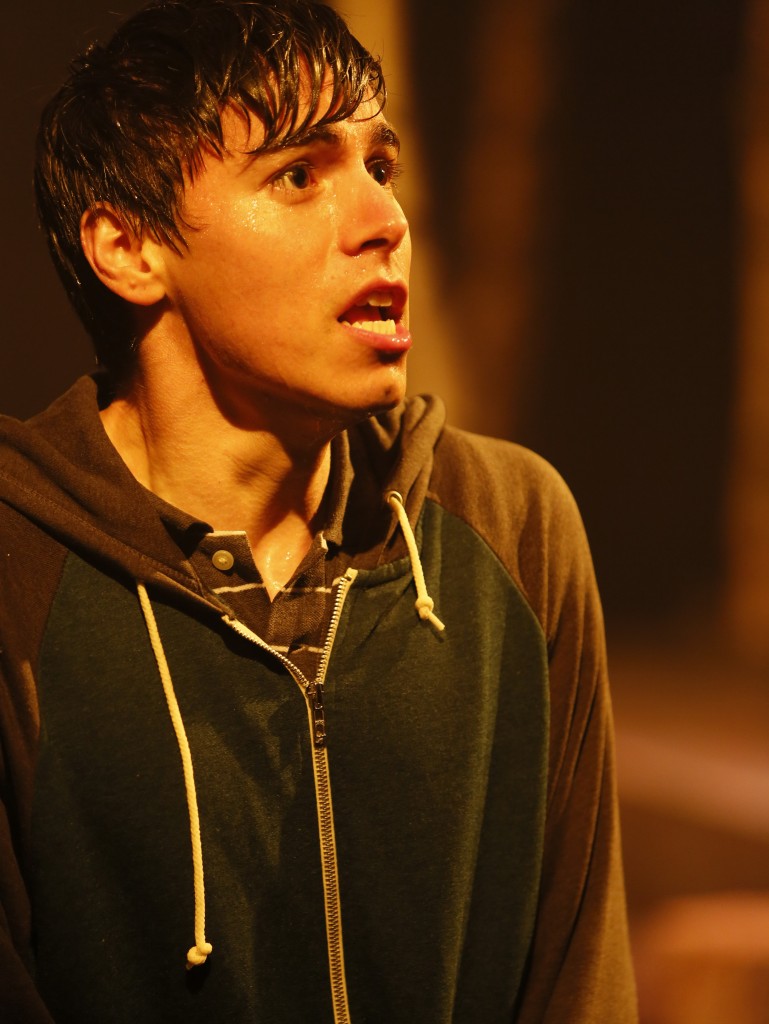

Richard Russ brings a welcome freshness and innocence to the role of Wolfie in the midst of such angst, sniping and hostility. His character’s quest for his First Nations roots is such a positive amidst so much negativity that the whole spirit of Indian Arm is lifted whenever he’s on stage. As in Little Eyolf, much of Indian Arm happens after the tragedy and deals with the aftermath. Is redemption or reconciliation possible under such circumstances?

Credit: Tim Matheson

Gloria May Eshkibok, an Odawa First Nations actor from Manitoulin, Ontario, grounds this play. She brings an elder’s wisdom and dignity necessary to get these characters to a place of forgiveness.

There’s a lot going on in Kanagawa’s play: old leases on unceded First Nations territory, residential school abuses, marital strife, abuse of the mentally challenged, searching for roots and response to personal tragedy – all interwoven. There’s not a lot of joy here but perhaps there’s a glimmer of hope for better things to come.

On a personal note: I have lived off and mostly on the Arm since I was eight years old. Like Rita, Wolfie and Alfred, I live on unceded First Nations land and, as the great, great grandchild of English immigrants, I am truly grateful for the privilege of sharing this land with its first people.

Little Eyolf is a difficult, seldom-produced play. It was Rumble’s artistic director Stephen Drover’s choice to adapt this particular play and to commission Hiro Kanagawa, who initially had reservations, to accept it. In his program notes Kanagawa writes: “It is not exactly a “faithful” adaptation of Little Eyolf but it has this in common with the original: both are plays about people struggling to redefine their connection to one another and to the world after they have been cast adrift. In this context I think I have been true to Ibsen, if not faithful.”