Credit: Phile Desprez

At the York Theatre until May 5, 2018

Tickets from $22 at tickets.thecultch.com or 604-251-1363

Posted April 27, 2018

I love Canadian theatre and how it reflects and challenges our values but it’s so stimulating to see something ‘from away’ – far away. The History of the World (Based on Banalities) comes from Belgium’s Kopergietery, a theatre company known for innovation and its focus on theatre for young adults (TYA). It seems that Belgian TYA is not like ours. The Cultch’s artistic director Heather Redfern writes in the press release, “Belgian artists treat youth as though they are adult enough to understand complex and difficult situations and ideas, which is abundantly clear as we see youth taking the lead on issues that matter most to our world today. It’s a show that works for both adults and young adults, because it does not differentiate between the two.”

History of the World is presented by The Cultch, Kopergietery, Richard Jordan Productions and Theatre Royal Plymouth in association with Summerhall and Big in Belgium, with the support of the Flemish Government, Province of East-Flanders and the City of Ghent.

Written by Johan De Smet, who also directs, and Titus De Voogdt, the (almost) solo performer, it weaves together physics, magic, rock music, storytelling, grief, the fruit of malus domestica (apples), the biggest pile of dirty dishes in a sink you can imagine and one red balloon.

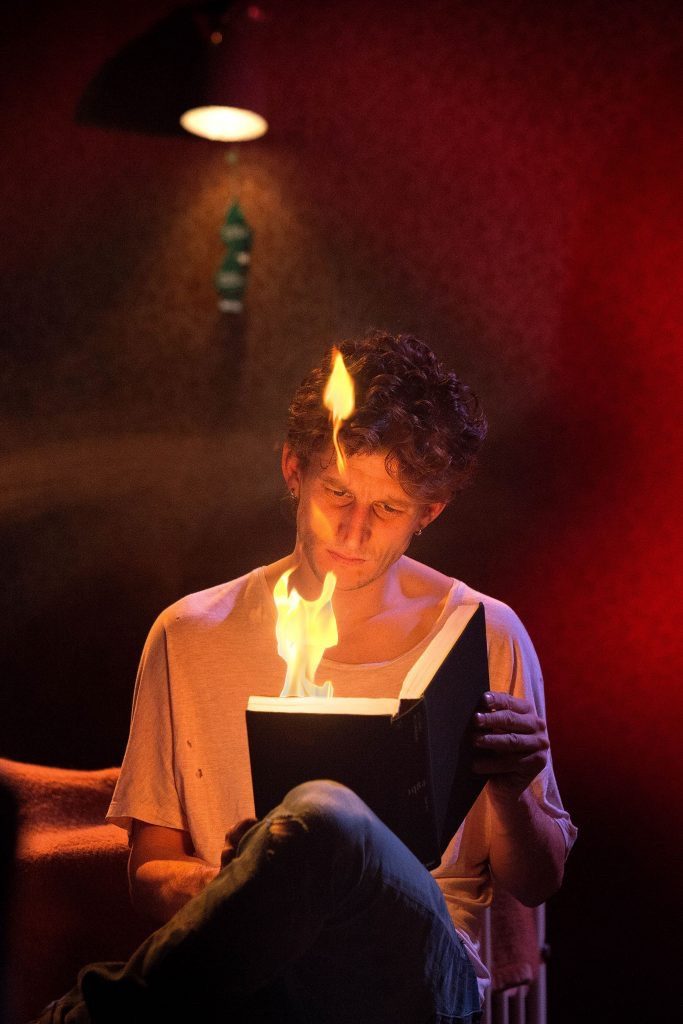

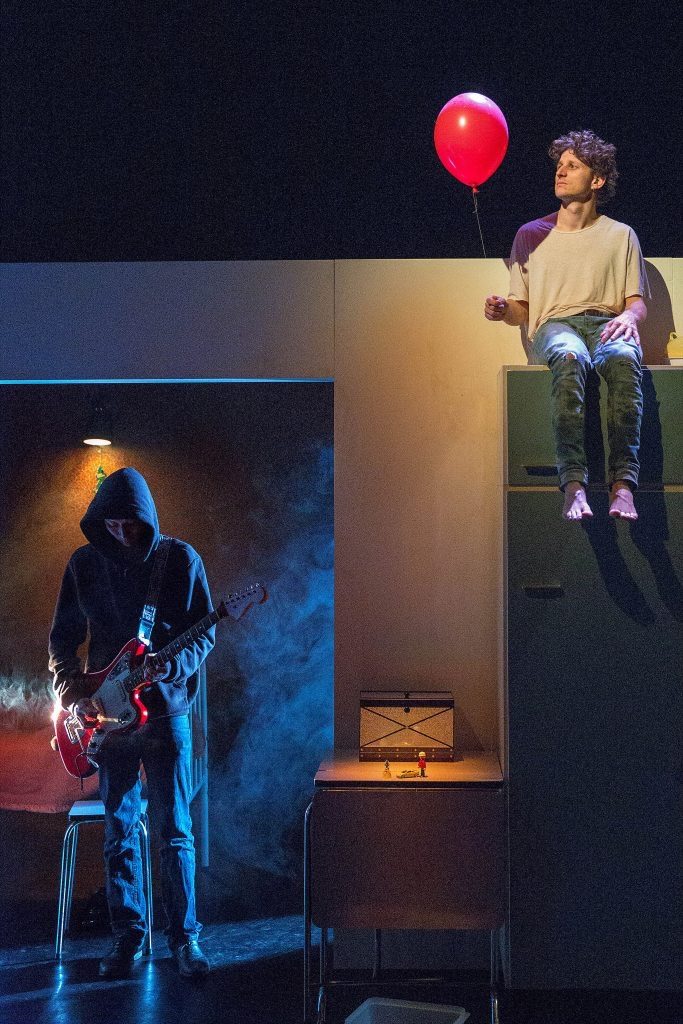

De Voogdt, in a soiled white t-shirt and jeans, plays a sort of Bolo Ball with a racquetball racquet and a rubber ball tethered to the floor on a rubber line. The ball flies crazily all over the place, including the front row of the York. A highly physical and energetic performer, barefoot De Voogdt nimbly hops up on the chrome and arborite kitchen table, the countertops, into and out of the broom closet and perches on the foot of the bed in which his mother, stricken with Alzheimer’s, lays dying. He makes tea, throws the teabag against the cupboard door where it hangs; he tosses his dishes in the sink, drops the racquet and leaves it where it falls. It feels as though the character, Philip, is desperately bored but desperately looking for something.

Credit: Phile Desprez

A famous physicist, Philip’s mother abandoned him when he was a boy and went to Switzerland to continue her quest for the Higgs boson particle – a particle that, apparently, holds the world together. Philip tries several times to explain the theory to us, but you don’t have to know anything about physics to understand this: Philip needs his mother to show some glimmer of love for him before she dies.

Rock musician Geoffrey Burton makes a few mysterious entrances: black hooded, accompanied by swirls of smoke and playing very loud, raucous electric guitar. Is he Death? We don’t know.

Death, Philip explains, is simply a matter of all the atoms that make up the human body deciding to “go away and become something else.” And while his mother’s atoms are making up their minds, Philip theorizes on all kinds of (sort of) unrelated ideas. Why do village churches appear to be sinking into the ground? They’re not, he says; it’s that with all those corpses buried in the churchyard, the ground is rising.

Credit: Phile Desprez

He also theorizes on Spanish fly which, apparently, is not a fly but a beetle that is parasitic in one phase and predatory in another. It ends up, Philip tells us, making you “incredibly horny.”

Philip entertains us with some magic tricks; one involves baking a cake, another, shooting a balloon with a shotgun. And he plays with the racquet and ball throughout.

The thing is this: will his mother – who, he tells us, “had no clue how to behave like a mom” – die before acknowledging him? He passes time, periodically going in to take a look at her. We see only the foot of her bed in the next room, her feet tucked in under the sheet. Back and forth, back and forth. He reads to her. Time passes. In one way, nothing happens; in another, lots happens.

The History of the World is undeniably quirky but it keeps you engaged in its off-beat examination of death and longing, physics and magic. It’s decidedly European in its sensibility and it offers a small window into what Belgians find theatre-worthy. Find a teenager and go together. And then talk. Maybe we’re selling our teenagers short. Maybe they understand that the Higgs field, unlike other known fields such as the electromagnetic field is scalar and also has a non-zero constant value in a vacuum. Damned if I do.