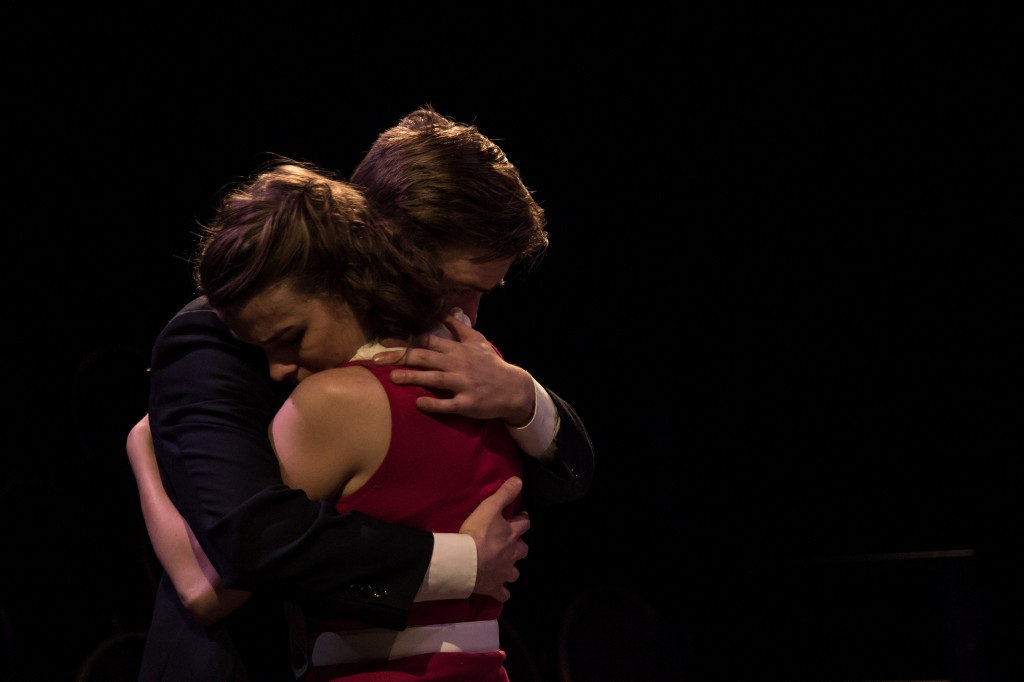

Credit: Matt Reznek/Bold Rezolution Studio

At Jericho Arts Centre until August 8, 2015

www.ensembletheatrecompany.ca

Posted July 26, 2015

If you faint at the sight of blood, take your smelling salts to ‘Tis Pity She’s A Whore or, if you’re able to tear yourself away from the play’s bloody dénouement, leave fifteen minutes before the end. Forget that; you won’t be able to.

Apart from the prodigious amount of gore, ‘Tis Pity She’s A Whore, penned by John Ford, circa 1629, is a fascinating barometer of the times. There are no extant reviews of the first production but, after seeing a performance in 1661, Samuel Pepys commented, “A foolish play, and ill-acted”. Theatres through the years have been prohibited from posting the title on the marquee or advertising in newspapers; sometimes the billing has read, “Annabella and Giovanni”, the incestuous brother and sister at the centre of Ford’s tragedy, to avoid using the word, ‘whore’. Censors and audiences, right up to the present, balk at using the original title. Striking up a conversation in a coffee bar, the woman beside me – observing me reading the script – remarked that she would never go to a play with ‘whore’ in the title.

Absolutely fascinating is the way directors have handled the physicality of the incestuous relationship. In Ford’s original, Giovanni and Annabella enter Act II Scene 1, “as from their chamber”. No bed, no fastening of trousers or adjusting of petticoats. At the other end of the spectrum is a 1977 Royal Shakespeare Company studio production in which Giovanni and Annabella “made love naked on stage.” Sign of the times?

In this Ensemble Theatre Production director Brian Parkinson takes a conservative but not prudish middle line: there’s a bed and brother and sister have obviously been ‘between sheets’. There might be a little puppy-ish tumbling but nothing more graphic than that.

Credit: Matt Reznek

Amazingly, the play feels quite relevant – mostly in its misogyny, gender double standard and hypocrisy – but even more so in raising contemporary questions about who is permitted (by law or societal taboos) to have sex with whom. In the play, the Friar (Matthew Bissett) argues that if Giovanni acts on his sexual desire for Annabella, it will go against God’s law. Giovanni, supposedly a scholar, argues that “Nature” – as opposed to God – would approve their relationship. Although Giovanni claims it would be “natural” for him to desire Annabella, we have known for a long time the disastrous results in the offspring of such liaisons, although royalty continued the practice for generations.

Contemporary arguments against incest are at least two-fold: genetics and power imbalance – especially in the case of, say, father and daughter, older brother and younger sister, mother and son, uncle and niece. But what if there are no offspring and the relationship is consensual and not coercive? What then?

But back to the play.

More questions. Whose play is it anyway? And how do we perceive Giovanni: a courageous rebel, prepared to take on God and society in order to have sex with his sister? But he lies to her to get her to confess her attraction to him. Hardly heroic. (He tells Annabella that the Friar gives his blessing when the cleric says, “Yes, you may love, fair son” but it’s completely out of context. The Friar meant Giovanni may love Annabella but not have sex with her. Eternal damnation lies that way.)

Credit: Matt Reznek

Under Parkinson’s direction, Maxamillian Wallace’s Giovanni is not rebelliously heroic but rather a petulant, unstable fellow who, in reaction to the many suitors that are seeking Annabella’s hand, lusts after her. Pure Freudian. Wallace, costumed in contemporary dress by Kiara Lawson, is intense, childish and peevish which adds to the tragedy being Annabella’s. Anthea Morritt, as Annabella, is far from whorish; she’s sweet, innocent and although Annabella is sexually excited by Giovanni, it’s unlikely he would have persuaded her without her understanding that they had the Friar’s consent. There’s no indication in the script or in this production that Annabella would have initiated it.

Although Giovanni is, apparently, the most frequently sought after role, the most interesting role is that of Vasquez, servant of Soranzo (swaggeringly played by Michael Shewchuk). Shrewdly portrayed by Tariq Leslie, Vasquez is the character that manipulates all the others. Leslie is so persuasive, it’s possible to believe at several instances that he has betrayed Soranzo. Perhaps the greatest tragedy in this play is the absolute devotion demanded and received by the upper classes of their servants.

Credit: Matt Reznek

A synopsis with the program would be useful especially as it would clarify the relationship between Hippolita (excellently played by Alexis Kellum-Creer) and Richardetto (Jordon Navratil) as well as Grimaldi (Ryan Scramstad) and the Cardinal (Daniel Meron). Rebecca Walters’ lusty Putana is very like the Nurse in Romeo; Adam Beauchesne’s Bergetto is a little over the top but the script certainly supports the idea that Bergetto’s an idiot.

Sound design by Darren Hales is lush, romantic and adds appreciably to the production.

With a cast of fifteen (even with some double-casting), it’s unlikely ‘Tis Pity She’s A Whore will be often produced so the Ensemble Theatre Company offers a rare and excellent opportunity. The play continues to be controversial and, in this age of sexual liberalism, to raise some very provocative questions. If, in contradiction to the Friar’s warnings, there’s no hellfire waiting, how do we deal with incestuous love? Is that now the love that dares not speak its name?

[Almost as interesting as the play is the Introduction to the Mermaid pocket edition; highly recommended either before or after seeing the play.]