At Russian Hall until February 8, 2015

604-684-2787/ticketstonight.ca

Posted February 5, 2015

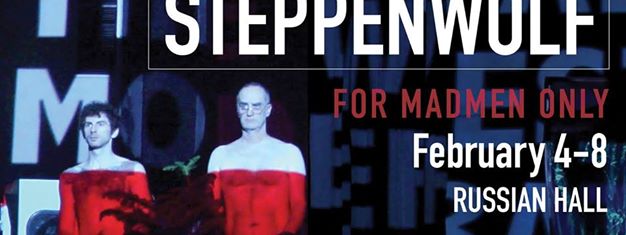

Bold. Ambitious. Audacious. These are words we sometimes use when we admire the attempt but don’t actually ‘get’ it. Steppenwolf, the debut work of Fight with a Stick theatre company co-founded by Alex Lazaridis Ferguson and Steven Hill (former artistic director of Leaky Heaven), is bold, ambitious and audacious.

But to begin with, it’s visually astonishing: the spectators enter the main room of the Russian Hall and instead of facing the stage are seated, with their backs to the stage, on low benches facing a long curtained area. When the curtain rises ever so slowly, the audience faces a long mirror – something like eight panels, 4’ x 6’ each. The action of the play actually takes place on the raised stage behind the benches and what the audience sees is a reflection of action. There’s a total of nine or ten performers/technicians, including Ferguson who appears – well, whose reflected image appears – in a tiny booth. Ferguson is reading aloud from Hermann Hesse’s Steppenwolf. It’s all very surreal. Sound of traffic. Sound of waves. Sound of ship’s horn. Glowing laptops float by. Nothing seems anchored.

First thing that comes to mind is Plato’s Allegory of the Cave: prisoners, held in a cave, are shackled facing the rear wall of the cave, preventing them from looking back to the sunlight outside. But between the sun and the cave entrance, the world carries on; images of this ‘real’ world are reflected on the rear wall of the cave. And the prisoners, unable to see the world outside, mistake these reflections for reality. Then one prisoner is released, discovers the ‘real’ – that is, the unreflected world – and returns to release the others – who refuse to go. Here’s a link to an animated version of Plato’s allegory: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d2afuTvUzBQ. It’s fun and will give you a useful approach to this show.

I found the connection to Hesse’s Steppenwolf less obvious but it’s been three or four decades since I read it. Hesse’s character, Harry Haller, views himself as torn between his spiritual self and his animal self – the wolf of the steppes. He’s an outsider, ill suited to the bourgeois world he finds himself in. If Ferguson’s reading of Steppenwolf is barely audible, it is completely inaudible when Nneka Croal takes over the booth (which we appear to be looking at but which, in fact, is merely a reflection.) Perhaps all we are supposed to hear are occasional words; maybe not.

Some of the imagery is fantastic: a little house, sheathed in clear plastic, bathed in changing light, and slowly rotating, is fantastic. And the lighting design is pure wizardry. There are times when very bright lights are turned on the audience whose reflection suddenly appears in the mirrors. A sense of inclusion is definitely striven for but bewilderment probably keeps most of the audience somewhat at arms length.

Upon reflection – pardon the pun – I started to think about TV, film, theatre and literature – and the possibility that we mistake these ‘reflections’ for reality. Certainly sitcoms set up unrealistic expectations of what life should be like; pornography has, apparently, set the bar so high that celibacy has become a choice and what used to be considered pretty good sex pales by comparison; men and women are expecting the impossible of their partners.

Are we, like Plato’s prisoners, confusing mere reflection with reality? And what sort of courage does it take to, metaphorically, leave the cave?

Ferguson and Hill are big, outside the box thinkers. Steppenwolf, part of the PuSh Festival, is visually amazing and, apparently, the ‘moving installations’ created by the performers are created according to each performer on the spot; no two performances will be alike.

The subtitle of the novel is For Madmen Only and this production is decidedly challenging. Perhaps, like The Magic Theatre of the novel – and I quote, “Entrance is not for everybody.”