Credit: Ryan McDonald

At Jericho Arts Centre until October 24, 2015

604-224-8007/brownpapertickets.com

Posted October 15, 2015

What strikes you right away is how modern A Doll’s House, written in 1879 by the great Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen, feels. The costumes, by Christopher Gauthier, may be beautifully ‘period’ – sumptuous gowns and fur-trimmed cloaks – but the complaint Nora (Genevieve Fleming) makes against her husband Torvald (Shaker Paleja) is heard every day between women in coffee bars and psychiatrists’ offices: “I feel like I’m living with a stranger.” The same admission is, undoubtedly, made by men. Indeed, Ibsen rejected the idea that he was an early feminist, claiming that he believed everyone should have the right to become what he or she was capable of becoming. Marriage can be the great challenge to self-realization.

In late 19th century Norway, marriage was more rigidly prescribed than it is today. Nora, treated like a doll in a doll’s house by her father, has been married to Torvald for eight years and borne three children. He patronizingly calls her “his little squirrel”, his “lark” and his “own precious little songbird”. Once again, Nora in her 30s is just another doll in another doll’s house. There’s a governess (Laura Jaye) to look after the children, a maid (Jaye again) and, no doubt, a cook.

Credit: Ryan McDonald

Nora seems to be spending her way out of boredom: Christmas decorations, toys for the children but little for herself. “My little spendthrift”, Torvald complains teasingly. Recently promoted to bank manager, the couple is on the verge of living very comfortably.

Nora, however, has a dark secret and in the play, the past catches up with her.

Fleming, under the direction of Tamara McCarthy, embraces all of Nora’s giddy desperation at the beginning of this great classic. Constantly in motion, Fleming flutters here and there, as if Nora is afraid to stop moving, chattering, smoothing her gown and fawning over Torvald. We see what Nora doesn’t: she does tricks like a well-trained dog to please him and pacify him over her need for money. Like her friend Mrs. Linden (Corina Akeson), you want to shake her, tell her to stop behaving like a child. But her frenzy and silly behaviour is rooted in the terror of her crime being discovered.

By the end of the play, however, Fleming finds dignity – even a kind of nobility – in Nora. There is great satisfaction in seeing Torvald, patronizing prig that he is, receive his come-uppance.

Credit: Ryan McDonald

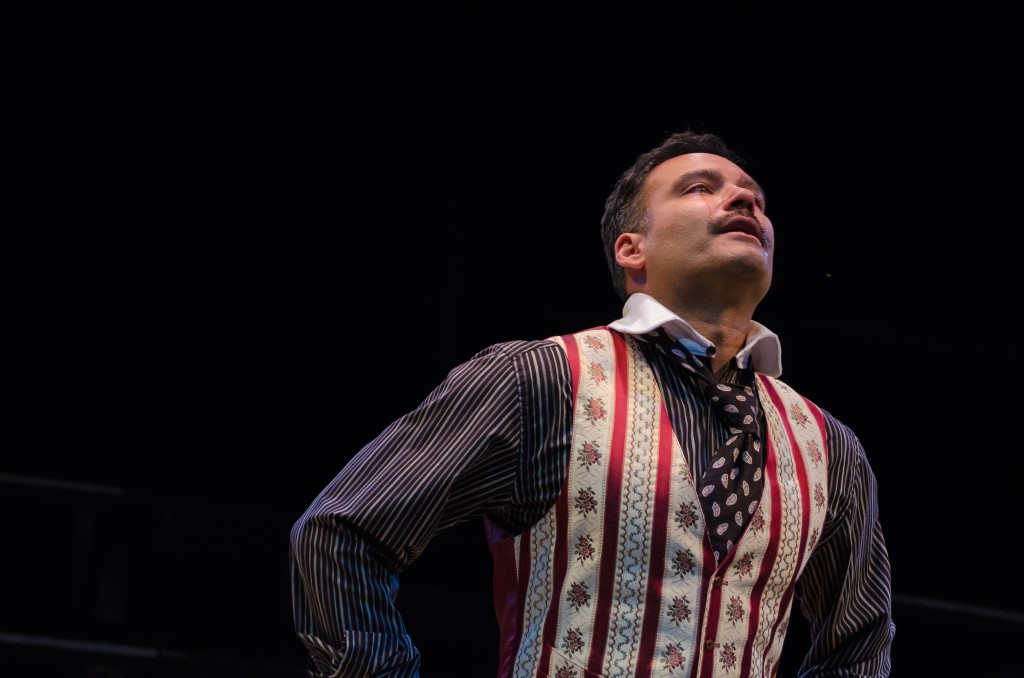

Paleja does well as chiding, constantly condescending husband Torvald, but it’s Sebastian Kroon’s Dr. Rank that’s really interesting in this production. The doctor is seemingly in the background of Nora and Torvald’s life. But here, Rank’s declaration of love for Nora is really poignant and her decision not to ask him for money indicates a kind of integrity in Nora that we have not seen in her before.

Krogstad (Ashley O’Connell), too, is painted with more empathy than generally seen. Driven by a past he has struggled with difficulty to rise above, Krogstad threatens Nora with disclosure but, while not condoning his threats, we understand his desperation.

There is almost always a do-gooding meddler in Ibsen’s play. Here it is Mrs. Linden who, with a solution for Nora within her grasp, decides – mistakenly or possibly not mistakenly – what is best for her friend. Akeson, last seen as ball-buster Dave Moss in the all-female Glengarry Glen Ross, is appropriately prim, earnest and manipulative.

Ibsen is celebrated as the father or godfather of modern drama/realism. In this play he has not completely abandoned the popular melodrama of the period but it is much more subtle.

A Doll’s House outraged 19th century audiences: women did not leave their husbands and they were certainly not encouraged to do so. Critics and scholars say the sound of Nora slamming the door behind her reverberated around the world.

Credit: Ryan McDonald

But Nora does not slam the door behind her; she shuts the door behind her – and that’s different. She does not leave in anger but in the sober realization that she has a right to her own life. Produced by The Slamming Door Artist Collective, this Nora leaves through a swinging door that slowly swings behind her until it stops. That’s surely the quiet, determined exit Ibsen had in mind for his heroine.