At The Cultch until October 24, 2015

SOLD OUT

Posted October 21, 2015

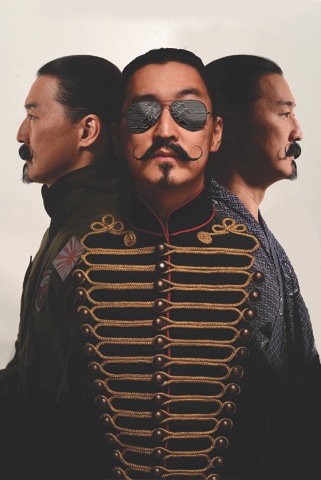

Writer/performer Tetsuro Shigematsu (the self-confessed “trouble son” of Akira Shigematsu) did not have a very good relationship with his father but he’s making up for it now. Night after night in the Vancity Culture Lab at The Cultch he admits he never said, “I love you” to his dad. He’s saying it now.

Shigematsu, a former writer for This Hour Has 22 Minutes and former host of Richardson’s Roundup on CBC, is now a writer for the Huffington Post and a PhD candidate at UBC where he also teaches creative writing. He’s a husband and a father of two. With all of that going on, Shigematsu has to be a master of the segue and he is.

The story of Shigematsu and his father leapfrogs all over the place from Hiroshima to London to Pointe-Claire and Vancouver. And the time goes back and forth between the present, back to August 1945 and the bombing of Hiroshima when his father was a twelve-year-old, to September 2015 when his father died.

Credit: Raymond Shum

Even as Shigematsu opens his heart to us, the show is punctuated with a kind of hip, clever humour. His mother, he says, wasn’t “devastated” when she discovered she was pregnant with him and his twin sister although she already had three children. And he’s quick to make fun of himself. Unable to cry, his says his kids say he’s a “sociopath”.

His story is fascinating: a legacy of Japanese male forbears all of whom remained close-mouthed as a way of dealing with tragedy and disappointment. His father was a radio host with the BBC and then CBC for years but ended up pushing a mail cart for the CBC. Most humiliating of all was being treated familiarly by everyone and being addressed, not as Mr. Shigematsu as he wished, but Akira.

Interesting as the story is, the best part is how inventively it is told. The journalist in Shigematsu has kept old photos and letters, has tape recorded conversations and he uses them here to create a rich documentary: himself, his twin sister and his three other siblings together as children in the bathtub; his family – including his very conservative-looking father – with Big Ben in the background; his recording of his father describing the incendiary bombing of his village and the complete destruction of the houses – just “wood and paper” – that burned fiercely as every man, woman and child ran from the flames.

But most innovative is his use of large, real-time videocam projections: a tiny paper boat in a dish of water projected as he films it; two fingers playing with a miniature skateboard underscored with a less-than-respectful conversation with his father; two fingers like a pair of skaters gliding across an imaginary frozen pond on Grouse Mountain. A syringe of a cloudy liquid squirted into a bowl of clear water erupts like a huge mushroom cloud on the screen. Like a Japanese painting, it’s all about the minimal strokes of the brush; our imagination fills in the rest.

Credit: Raymond Shum

Pam Johnson’s set is shoji-screen inspired with a confusion of wooden stakes – like a post-apocalypse village – overhead. Lighting designer Gerald King transforms Johnson’s set with a vast palette of lighting effects.

Shigematsu has not yet cried for his father and worries that, after a life of conflict with him, he will not be able to shed tears when the funeral comes around. With each performance, through the dredging up of old memories, he comes closer to resolving his troubled relationship and his inability to open himself to grief. Painful as it is to grieve for one we love, how much more difficult it is to grieve for one with whom we were emotionally distant but loved, nevertheless.

Directed by Richard Wolfe, produced by Vancouver Asian Canadian Theatre and presented by The Cultch, Empire of the Son is jewel-like in its sparkle and perfection. The first week was sold out before it opened; extended for a second week, it sold out almost immediately. With such success, there’s hope for a remount. Don’t miss it if it comes again.

Credit: Raymond Shum