Credit: David Cooper

At The Stanley until October 13, 2019

Tickets from $29 at artsclub.com or 604-687-1644

Posted September 20, 2019

Act 1 of A Thousand Splendid Suns made me so angry, I felt my blood beginning to boil. It validated my hostility toward certain fundamentalist Islamic regimes: the subjugation of women, the domination of husbands over their wives, the denigration of female babies and much more. Eventually, however, I was able to put the story into a specific context: Kabul, Afghanistan in the 1990s under the repressive Taliban regime. Rasheed (Anousha Alamian), the villain of the story, is a product of that culture – not that it excuses him but it does explain him.

Credit: David Cooper

More than that, A Thousand Splendid Suns is about the unlikely friendship between two women: Rasheed’s older first wife Mariam (Deena Aziz) and his teenaged second wife Laila (Anita Majumdar).

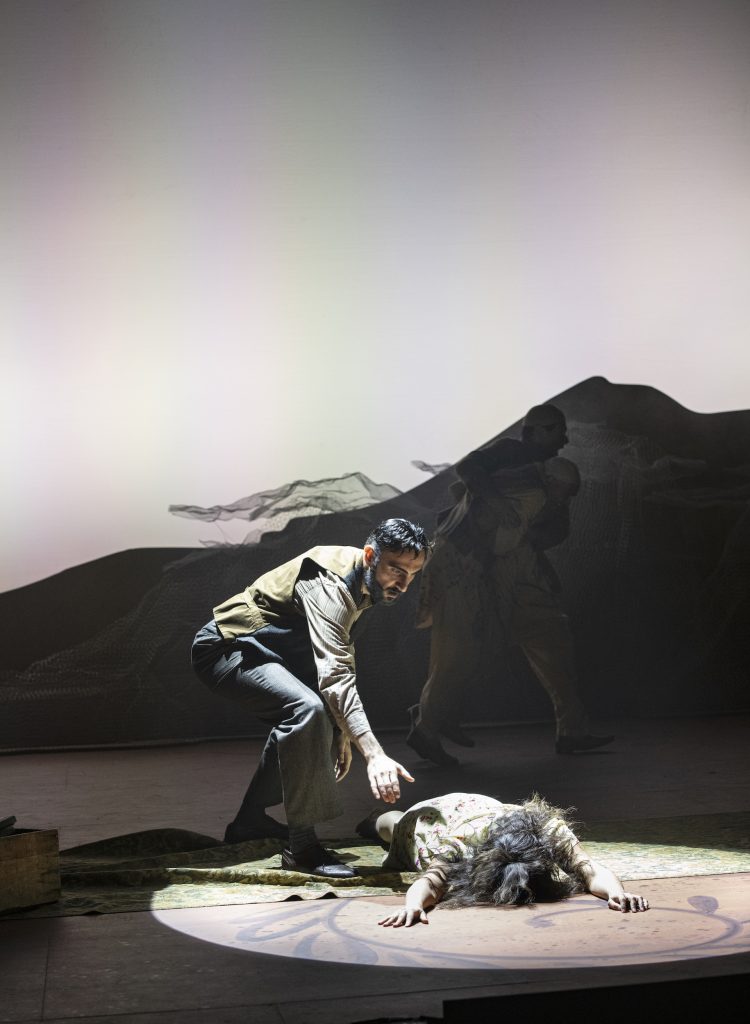

The play is an adaptation by Ursula Rani Sarma of Khaled Hosseini’s novel of the same name. And perhaps in the process of adaptation, nuance is sacrificed. In the play, Rasheed is completely one-dimensional; while he claims all he wants to do is protect Laila, orphaned when her parents perish in a bomb strike, it is obvious Rasheed simply wants a second, younger wife (hopefully a breeder of sons) and fifteen-year-old Laila is vulnerable. He and his wife Mariam take Laila in and to “legitimize the situation”, as Rasheed puts it, he marries her. Soon Laila is pregnant and there is a baby – not Rasheed’s longed-for son but a daughter – and soon there are beatings with his belt and threats against the newborn.

The characters of Mariam and Laila are more fleshed-out – especially Mariam. We see her in flashbacks as a high-spirited young girl, eager for the affection of her father but eventually simply married off to Rasheed against her will. We see miscarriages, mistreatment and the indignity of having to accept young and pretty Laila into her household. Rasheed even takes the wedding ring he gave to Mariam and has it re-worked for Laila with the callous rationale, “she never wears it anyway.”

In the face of brutality, Mariam and Laila form a bond and hatch a plot to escape Rasheed.

Credit: David Cooper

Co-produced by the Arts Club Theatre and the Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre, A Thousand Splendid Suns is unapologetically melodramatic. Apparently, in the London production, the character of Mariam was played for some humour with “skulks and scowls”, according to Guardian reviewer Arifa Akbar. Directing this production, Haysam Kadri makes no such mistake.

Deena Aziz, as Mariam, is initially cold and hostile toward Laila but Aziz brings Mariam slowly to warmth especially after the birth of Laila’s baby daughter. It is both heartbreaking and heartwarming to see Mariam take the crying infant and lull it to sleep. And while we find it difficult to accept the sacrifice Mariam eventually makes, Aziz does it with such dignity and compassion that we accept the choice her character makes.

Credit: David Cooper

Laila’s backstory is brief but telling: she comes from a liberal Moslem home with a loving father, lots of books and opportunity. As young Laila, Anita Majumdar is girlish, happy, full of life. Later, even risking Rasheed’s fury, Majumdar shows Laila’s unbroken spirit as she protects both her infant child and Mariam.

In counterpoint to Rasheed’s brutality are Laila’s father Babi (Munish Sharma) and Tariq (Abraham Asto) – two loving, caring men who are opposed to the strictures against women. Without these two characters, A Thousand Splendid Suns would be bleak indeed.

Set design by Ken MacDonald is sometimes obtrusive with its backdrop of stylized sun, flowers (or leaves) and mountains. When at its simplest, however, it is gorgeous and beautifully illuminated by Robert Wierzel and Andrew F. Griffin. Costumes – lots of Middle Eastern cotton trousers, tunics and eventually full-cover black burkas – are by Linda Cho and Alison Green.

Set design: Ken MacDonald

Credit: David Cooper

A Thousand Splendid Suns strives for a hopeful ending but it’s hard to overlook the fact that while progress is being made, in some parts of the world women and girls are still subjected to forced marriages, prohibited from attending school, prevented from leaving their home unless attended by a male relative, covered from head to toe and stoned for adultery sometimes after being raped.

There’s a happy ending for Laila and her children but it’s difficult to leave the theatre feeling optimistic because Laila’s story is the exception, not the rule.