Credit: Shimon Karmel

At Studio 16 until November 19, 2016

mitchandmurrayproductions.com

Posted November 6, 2016

Written by Lisa D’Amour, Detroit is a scorching, darkly funny look at the unravelling of the American middle class and what the consequences might be.

Somewhere in America – not necessarily Detroit – Ben and Mary’s barbecue (that emblem of the comfortable, middle class) still works but the automatic lighting device has quit. The patio umbrella keeps toppling over; the sliding glass doors leading out to the patio keep jamming; and the patio deck is falling apart.

The backyard patio party and the bacon-wrapped appetizers that Mary has made for her guests hearken back to a past era when neighbours were neighbourly and dads came home from work, greeted by kids rushing out to meet them in the driveway. Things worked. Husbands had jobs.

Ben (Joel Wirkkunen), a loans officer in a bank, has just lost his job; Mary (Jennifer Copping) works as a paralegal but she won’t be able to cover the mortgage on their bungalow along a street of similarly nondescript suburban bungalows.

Credit: Shimon Karmel

But Mary and Ben – especially Mary – keep up appearances and invite new, young neighbours Sharon (Luisa Jojic) and Kenny (Aaron Craven) over for dinner. Sharon and Kenny met when they were in rehab for drug abuse but, obviously, their rehabilitation isn’t complete: Sharon can’t keep her hands off Kenny and is an anxious, non-stop talker. She blithers on with a lot of pop psychology about “opening up” to one’s inner feelings. Jojic’s Sharon is a little bit skanky, a little bit pathetic and she simply vibrates with nervous energy. Kenny tries to keep the lid on her. A tall and dominating presence on stage, Craven swings from keeping Kenny barely under control to letting Kenny off-leash. “He’s at zero; anything can happen”, Sharon excitedly tells Ben and Mary.

Ben and Mary are more like us: doing their best. But she drinks too much and Ben doesn’t appear to be making much headway on his proposed website. Copping gives us a tremendously nuanced performance as Mary, desperate and fragile as her formerly secure life implodes. Copping looks like she’s made of glass. Wirkkunen’s Ben tries to bluff his way through the crisis but cracks are beginning to show.

One of D’Amour’s themes is the conflict between our wild and our civilized sides. Mary and Sharon think camping out will reconnect them to their inherent but suppressed wildness; Ben and Kenny look to a night of drinking and, probably, chasing women. Both plans fail to materialize but the desire to cut loose remains. Maybe a plain old bacchanalia will have to suffice; cue the orgy.

Credit: Shimon Karmel

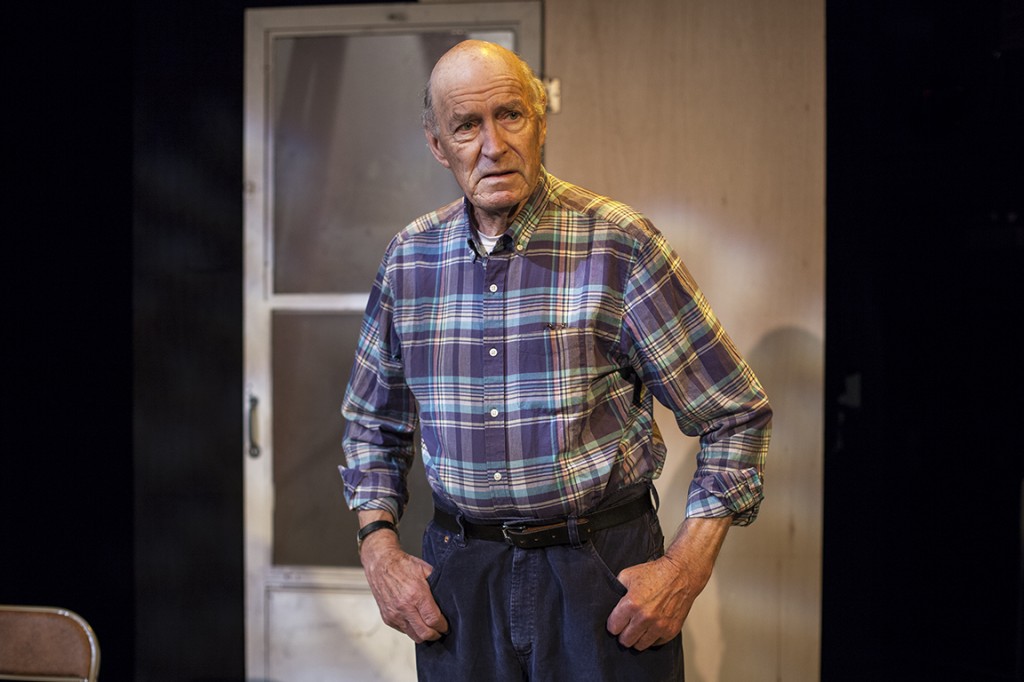

Directed by Lois Anderson for Mitch and Murray Productions, the performances, including John R. Taylor (as Frank, the owner of the house in which Kenny and Sharon live) are superb. While it’s true the characters are presented more like caricatures – with the possible exception of Frank – the issues resonate so strongly it really doesn’t matter.

David Roberts provides a functional set: two adjacent backyards with furniture that’s just barely hanging on. Lighting designer Conor Moore frees his inner child. See the play; you’ll see what I mean.

Detroit is not a play you like; it’s a play that makes you think. Does the thin veneer of civility crack as the middle class erodes? And when that veneer is gone, do our animal instincts take over? These are not new questions but they are intelligently posed.

Imagining the future can be depressing but as Frank says, the past might not have been as good as we choose to remember it was. Is nostalgia “just a defense mechanism in a time of accelerated and fragmented rhythms of life and historical upheavals” as opined in an article in the Concordia Undergraduate Journal of Art History (dug up by my savvy guest who reads such articles)?

I remember when nostalgia was respectable. Those were the days.

Credit: Shimon Karmel