Credit: Tim Matheson

At Little Mountain Theatre (26th & Main) until April 6

brownpapertickets.com

Posted March 30, 2014

Many of us remember the TV coverage of the looting of Baghdad’s National Museum of Iraq in the Spring of 2003. Perhaps by the time we saw the news the most precious artifacts had already been stolen because what I remember seeing were men and boys running out with chairs, bookcases and small tables. I wondered what they planned to do with such ordinary items. So naïve am I that I didn’t realize that anything carried out could be sold on the street – even filing cabinets.

The priceless stuff – artifacts going back as far as 7,000 years to Babylonian, Assyrian, Akkadian and Sumerian civilizations – had probably already been plundered and sold to American troops, wealthy Iraqis or international collectors before we saw the news. There was no shortage of buyers for these irreplaceable treasures. As it turns out, not as much was plundered as was first reported because the museum staff had taken precautions to hide some of the most precious stuff.

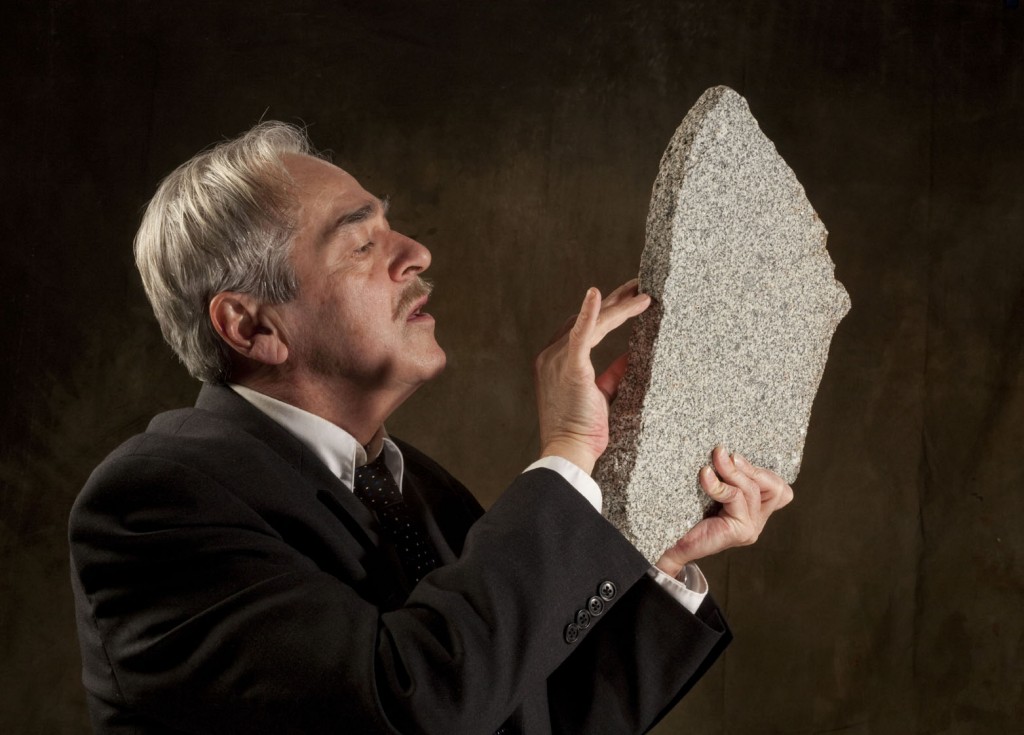

In this second play enjoying its world première in the last couple of weeks in Vancouver (Helen Lawrence was the first), playwright Michelle Deines takes us inside the museum. It is 2014, the museum has rarely opened since 2003 and a continuing effort is being made by the museum director Khalil Najim (Alec Willows) to purchase what stolen or found treasures come his way. Some are fakes, some are not.

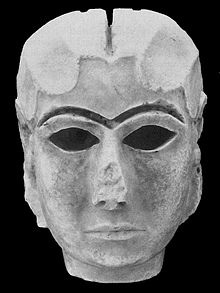

When a street kid who calls himself Dawood (Gili Roskies) turns up saying he has the Mask of Warka, dating back to 3100 BC and considered one of the earliest realistic representations of the human face, Najim is overjoyed. He strikes a bargain (300,000 dinars or about $3000 US) with Dawood and the mask is delivered the next day. Strangely, Najim’s assistant and former student Malika al-Nadi (Sarah May Redmond) discourages Najim from tests that would confirm its authenticity. This is the first little blip in Ghosts In Baghdad that doesn’t ring true.

Black marketer Hamza al-Qasim (Joshua Drebit who, as Hamza, seethes with menace and barely controlled rage) is behind this transaction and has an undisclosed hold over Dawood who turns out to be a young woman. Second little blip. We all know it’s a woman so why doesn’t Najim? He’s old but he’s not blind.

A third little hitch is Malika’s curious transition from her Act 1 shy, awed behaviour around Najim to her almost bossy attitude towards him at the beginning of Act 2. It took me a while (and a hasty look at the program) to be certain that the doe-like Malika from Act 1 was the assertive, hijab-wearing Malika in Act 2.

But under the direction of John Murphy and with some excellent lighting effects – like flashes from exploding bombs – by Darren Boquist, exotic Middle Eastern sound design by Jordan Watkins and excellent projections by Corwin Ferguson that take us right inside the museum, this is a fine first production of an interesting script.

Credit: Tim Matheson

Alec Willows makes Najim an eccentric but lovable archaeologist, known to his students as The Epic Poet because of his tendency to burst into verse from Homer to Keats. Redmond, apart from her quick transformation between acts, lends an air of caring and nurturing that extends from Najim and the museum itself to Dawood/Noor.

Ghosts in Baghdad, produced by Working Spark Theatre, gets a little ‘TV thriller’ at the end towards which the play seems to rush but the material is compelling.

Little Mountain Theatre is tiny and in its present configuration probably squeezes in 50-60 theatregoers. Go early to make sure you have good sightlines. While you wait, you can have a beer or a glass of wine that you can take into the theatre. Like ancient Babylon with its famous Hanging Gardens, it’s all very civilized inside Little Mountain Theatre.

Credit: Tim Matheson