Credit: David Cooper

At The Stanley until November 23, 2014

604-687-1644/artsclub.com

Posted October 31, 2014

The buzz before the opening of the Arts Club production of St. Joan went, “If anyone can breathe life into George Bernard Shaw’s 1924 script it will be Kim Collier” (one of Canada’s most exciting and innovative directors) “and Meg Roe” (as Joan, The Maid of Orleans.)

But that excited hubbub was a mere murmur compared to what audiences will be saying after they experience this stunning production. It’s a true spectacle with soldiers roaring up the aisles and scaling the walls of the balcony; lines of silent, hooded priests in white robes tolling bells; clerics in shimmering pearl-encrusted satin or sumptuous fur robes and soldiers in silver breastplates – all designed by Christine Reimer; a pair of singers (Christine Quintana and Shannon Chan-Kent) placed in the ‘Juliet’ balconies stage left and right, chanting and singing sound designer/composer Alessandro Juliani’s evocative score. It’s all about Church and State in all their pomp and circumstance pitted against Joan, a simple country girl whose ‘voices’ tell her she must drive the English out of France and put the Dauphin (later King Charles) on the French throne.

Director Collier has accomplished what I believe Shaw had in mind: a balanced perspective. He argues in his witty fifty-five page Preface to the play that Joan got a very fair trial, that the Inquisitor did not go beyond the bounds of his authority and that Joan was condemned for heresy and, according to the definition of the time, she was a heretic. While Joan was an accomplished military strategist – amazing in itself for a country girl who, like most women of the period, could not read – she did not grasp the fundamental argument of the Catholic Church: God did not speak directly to individuals like Joan but only through the Pope. The second charge – that she refused to wear women’s clothing – was her defence against rape while fighting with and sleeping alongside soldiers. But it was enough to condemn her because cross-dressing was a crime, even though when it was deemed necessary, it was not.

Credit: David Cooper

St. Joan is a stimulating, thought-provoking play and Collier gives it full, epic treatment. While the costuming and language is medieval, the text is delivered with a contemporary flair in a way makes the religious/political arguments comprehensible in spite of their wordiness.

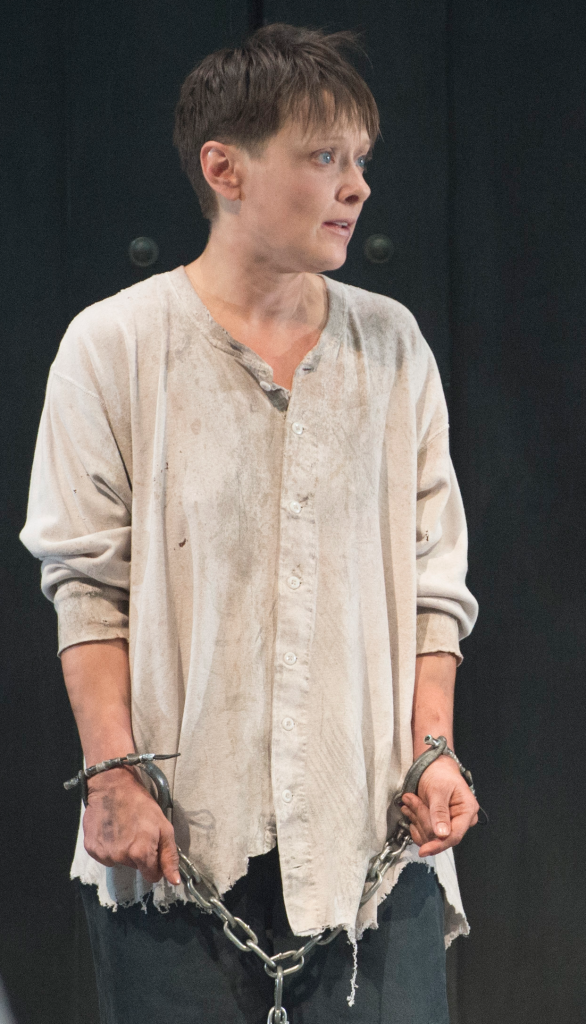

Meg Roe’s Joan could be a playground tomboy: sparky, dynamic, full of joie de vive and self-confidence. Roe often runs onstage; in Act 1 she’s in a long, bright red dress and modest white cap when Joan excitedly rushes into her meeting with Robert. In Act 2, Roe is dressed in armour, exuding soldierly assurance. Of course in Act 3, during the trial, Roe is in chains and rags when Joan’s spirit all but broken. It’s a wonderful performance and director Collier brings Joan/Roe back in the heavily cut Epilogue to lift our spirits after the inevitable and horrifying execution.

There are too many wonderful performances to note all of them: Scott Bellis, first as the Chamberlain and, later, as Bishop Cauchon; Haig Sutherland as the weak and disheartened Dauphin; Dean Paul Gibson, looking very Henry VIII, as the Earl of Warwick; Tom McBeath as the Inquisitor who tries desperately to make Joan understand what is really happening.

Credit: David Cooper

All this history unrolls on Pam Johnson’s masculine, military set: three tiered platforms that rotate against a backdrop of black, riveted panels that move aside in various configurations. Lighting by John Webber matches the grand scale of this production.

Is St. Joan a feminist play? Much more than that, it’s a humanist play that comments on the perils of individuals who put their lives at risk to make the world a better place. Shaw’s final words ring provocatively, disturbingly and not merely from a religious perspective: “When will the world be ready for our saints?”

Credit: David Cooper