Credit: Guntar Kravis

At Gateway Theatre until April 15, 2017

604-270-1812/gatewaytheatre.com

Posted April 8, 2017

How much you enjoy The Watershed might depend on whether you say ‘oil sands’ or ‘tar sands’. Generally, according to one of the characters in Montreal playwright Annabel Soutar’s play, those who favour extracting and processing the viscous mixture of sand, water, clay and bitumen at great cost to the environment say ‘oil sands’; those who think the black stuff should be left in the ground call it ‘tar sands.’ Whatever you call it, scientists conclude it is a threat to the purity of Alberta’s fresh water.

Co-produced by Porte Parole (Montreal) and Crow’s Theatre (Toronto) and presented by Gateway Theatre, The Watershed is ‘verbatim’ or ‘documentary’ theatre drawn from actual letters, documents, scientific papers and interviews. It’s packed with personages too many to remember from Dr. Henry Venema, vice-president, business development, International Institute for Sustainable Development and Dr. David Schindler, University of Alberta, freshwater scientist, to Maude Barlow, national chairperson, Council of Canadians and Kennedy Stewart, MP Burnaby South. Act I is an overload of information but it’s always made visually compelling by video projections, smart staging and superb performances.

Credit: Guntar Kravis

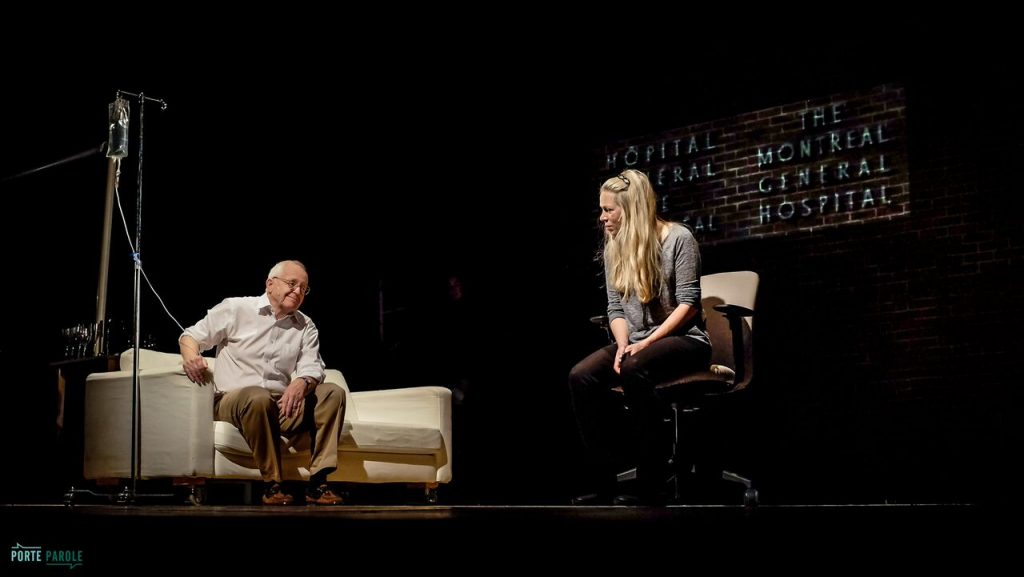

Chief among the performers is Liisa Repo-Martell who portrays Annabel Soutar, the playwright herself; Alex Ivanovici portrays – and actually is – Soutar’s husband Alex; and Eric Peterson takes on a multitude of roles including Soutar’s pro-energy father and a plumber called, at the top of the play, to deal with a flood in the Soutar/Ivanovici home.

The plumber’s visit leads Annabel to think about where water comes from, how it gets to our houses and ultimately, through a circuitous path more akin to investigative journalism than playwriting, to the Experimental Lakes Area (ELA) southeast of Kenora, Ontario, where since the late 60s, studies have been conducted to study water pollution. ELA studies were de-funded by the Harper government in 2012 then picked up by International Institute for Sustainable Development; in August 2016 (after Soutar wrote the play), the Trudeau government promised partial reinstatement of the original $2M funding to the tune of $1.5M.

The Watershed is a torrent of who said what and when. But Annabel is like a dog with a bone and the play is as much about her doggedness in getting answers, the effect her passionate fixation has on her family – husband, daughters Ella (10), Beatrice (8) and dog Charlotte as well as her very conservative parents – as it is about turning the material into a play.

In Act II the whole family, the dog and the girls’ friend Hazel pile into a Winnebago and drive across the country to Fort McMurray to see the oil sands.

Projections designer Denyse Karn keeps the upstage, faux-brick wall constantly interesting with snow and rain falling, landscapes whizzing past, banners and buildings. Scene changes are quick and completely fluid. There’s humour in the family dynamic: Ella (Molly Kidder) and Beatrice (Virgilia Griffith) bicker the way kids do but eventually they even do some interviewing. And we see Annabel’s frustration and near-meltdown when important interviews are suspiciously cancelled or when scientists clam up. The whole ‘play-making’ enterprise is laid wide open; even the director Chris Abraham is a character.

Credit: Guntar Kravis

Brenda Robbins, whose Hedda Gabler here in Vancouver years ago remains unforgettable, makes an eager-beaver, up-chucking Hazel with adolescent physical awkwardness; she’s completely believable as principled Maude Barlow and hilarious as a FOX News weather gal. Best line in the show goes to Robbins when Annabel’s Conservative mother snaps, “Don’t say that name in this house” upon hearing Naomi Klein’s name mentioned.

Multi-cast Bruce Dinsmore makes a very smooth Stephen Harper and Kimwun Perehenic appears in multitude of roles including Hazel’s mother.

In a 2015 interview the playwright is quoted as saying, “My attempt is to be rigorous and even-handed. No one can be 100 per cent objective. I attempted to speak to people on all sides, to have an open dialogue, but sometimes my attempts failed.” There’s no disguising the fact that Soutar is on the side of evidence-based science but that’s the right side to be on, right?

Annabel’s relationship with her father, thoughtfully played by Peterson, is complicated: father and daughter could hardly be further apart politically but there is love and respect on both sides. Annabel stumps her father with the question many of us might ask: what if our country’s policies were not determined by economists but, say, “by doctors”? Why not philosophers, artists or writers? Would we knock Norway off the Happiest Nation in the World pedestal and put Canada there? Naïve? Maybe. But why not?